From Grand Slam finals to year-end rankings, Eastern European players have shaped women’s tennis for more than two decades. But is this dominance accidental — or structural? By examining performance data, development models, physiology, and historical context, we can better understand why the region continues to produce elite champions at an exceptional rate.

The Numbers Behind the Narrative

The dominance of Eastern European players in women’s tennis is not a short-term anomaly — it is a long-standing statistical pattern.

Take the 2026 Australian Open as a recent example. From the quarterfinal stage onward, the share of Eastern European players increased in clear progression:

- 50% of quarterfinalists

- 75% of semifinalists

- 100% of finalists

This snapshot reflects a broader structural trend.

As of early 2026:

- Half of the WTA Top 10 consists of players from Eastern Europe.

- Over the past 20 years, an average of five Top 10 players per season have come from the region.

- In 2008, the Top 10 was almost entirely composed of players with Eastern European origins, with only Serena and Venus Williams breaking the pattern.

The dominance extends to Grand Slams:

- Over the last two decades, Eastern European players have won 28 major titles — more than one-third of all Slams played during that period.

- Eight players from the region (Sharapova, Azarenka, Halep, Kvitová, Świątek, Krejčíková, Sabalenka, Rybakina) have won multiple majors.

- Between January 2005 and January 2026, 51 of 80 Grand Slam finals (64%) featured at least one Eastern European player.

- In 11 of those finals (roughly 25%), both finalists came from the region.

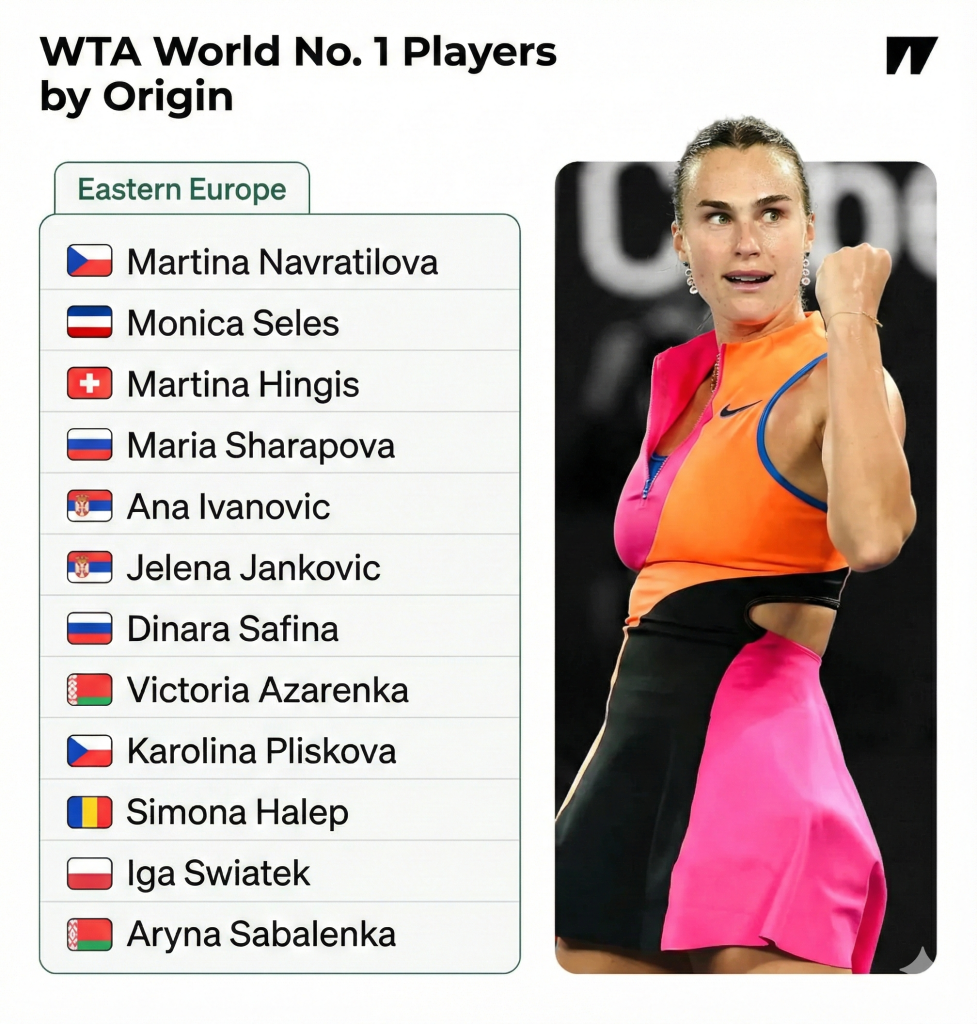

Historically, the trend is even stronger. Since the creation of the WTA rankings 50 years ago, 43% of world No. 1 players have been born in Eastern Europe (including countries of the former Eastern Bloc and Yugoslavia).

For comparison:

- Western Europe: 29%

- United States: 21%

- Australia: 7%

- Asia: 1 player (Naomi Osaka)

These figures include players whose professional careers later developed under different flags but whose formative tennis education occurred in Eastern Europe (e.g., Martina Navratilova, Monica Seles, Martina Hingis).

The pattern is not random. The question is why.

Physiology: Height as a Competitive Multiplier

One measurable factor is anthropometry — specifically average height.

Average female height in several Eastern European countries:

- Czech Republic: 168 cm

- Serbia: 168 cm

- Russia: 166 cm

- Poland: 165 cm

By comparison, the average female height in the United States is approximately 161 cm.

In modern women’s tennis, physicality has become increasingly decisive. A powerful serve is often described as “half the match,” and reach, leverage, and wingspan matter more than ever. Taller athletes generally generate higher serve velocity and steeper angles.

The 2026 Australian Open finalists Aryna Sabalenka and Elena Rybakina — among the tallest players in the Top 10 — are also two of the most powerful servers on tour. Last season, Rybakina averaged 171 km/h on first serve; Sabalenka averaged 168 km/h.

Height alone does not produce champions — but in an era defined by baseline power and first-strike tennis, it amplifies competitive advantage.

Technical Foundations: The Eastern European Training Model

Physical attributes explain only part of the equation.

Historically, Eastern European coaching systems emphasized:

- technical precision

- repetitive drilling

- structured stroke development

- disciplined biomechanics

In contrast:

- The American system traditionally prioritized tactical adaptability and athletic improvisation.

- The Spanish model emphasized movement, endurance, and clay-court resilience.

The timing of global tennis evolution worked in Eastern Europe’s favor.

The early 2000s — when players from the region began entering the WTA Tour in large numbers — coincided with surface homogenization. Courts slowed down, serve-and-volley declined, and baseline consistency became central.

As The Athletic has noted, “Serve-and-volley fell out of fashion because players became extremely effective at returning from deep behind the baseline.”

This shift favored technically sound, rhythm-based players who thrived in extended rallies — precisely the skill set emphasized in Eastern European academies.

The result: a generation prepared for the tactical demands of modern tennis.

Historical Context: From Restriction to Opportunity

To understand the psychological dimension, historical context is essential.

During the Cold War era, tennis in much of Eastern Europe was underfunded, restricted in international travel, and often considered a bourgeois sport. Only a handful of elite players emerged — mainly from Czechoslovakia or through emigration (Navratilova, Seles).

After the fall of socialist regimes in the 1990s, a structural shift occurred:

- Access to international tournaments expanded.

- Exposure to global coaching methodologies increased.

- Private academies and sponsorship channels developed.

For the first time, a large cohort of Eastern European players could compete globally from junior level onward.

This created not just opportunity — but momentum.

Competitive Identity: Discipline and Mental Hardness

Beyond physiology and technique, many analysts point to competitive psychology.

Players from Eastern Europe often describe their upbringing in demanding environments — socially, economically, and athletically — as formative.

Aryna Sabalenka once stated:

“I think we all grew up in tough conditions. We are strong people. We are fighters. It wasn’t easy for me — I always fought for my dream.”

Maria Sharapova famously described her mentality this way:

“I never give up. You can knock me down ten times, and I will get up the eleventh and hit that yellow ball right at you.”

While these statements are individual perspectives rather than universal truths, they reflect a broader cultural narrative: resilience, discipline, and emotional intensity.

However, it is important not to oversimplify. Success in modern tennis also comes from alternative models — including systems that prioritize emotional balance and athlete well-being. The recent resurgence of players who stepped away to focus on mental health demonstrates that multiple developmental pathways exist.

Eastern Europe’s dominance is therefore not a rigid formula, but a combination of structure, opportunity, and adaptation.

Structural Momentum, Not Coincidence

When evaluating 20-year trends across rankings, titles, and finals, the conclusion is clear: Eastern Europe’s dominance in women’s tennis is structural rather than accidental.

It is driven by:

- favorable physical attributes within the talent pool

- technically rigorous early training systems

- alignment with modern surface speeds and tactical trends

- post-1990s globalization of opportunity

- competitive identity shaped by demanding developmental environments

The outcome is visible not just in isolated champions, but in sustained depth across generations.

Conclusion: A Global Sport Shaped by Regional Strength

Women’s tennis today is globally competitive — and no single region has a monopoly on excellence. Yet Eastern Europe’s influence over the past two decades has been undeniable.

The reasons are not mystical. They are measurable, historical, and systemic.

Whether that dominance continues into the next generation will depend on how other regions adapt — and how Eastern Europe evolves in response.

What remains certain is this: when the biggest matches unfold on the sport’s grandest stages, Eastern European players are overwhelmingly present — and increasingly central to the modern identity of women’s tennis.

If you would like more data-driven analysis and weekly updates from the WTA and ATP Tours, explore our full tennis coverage in the news section of our portal.